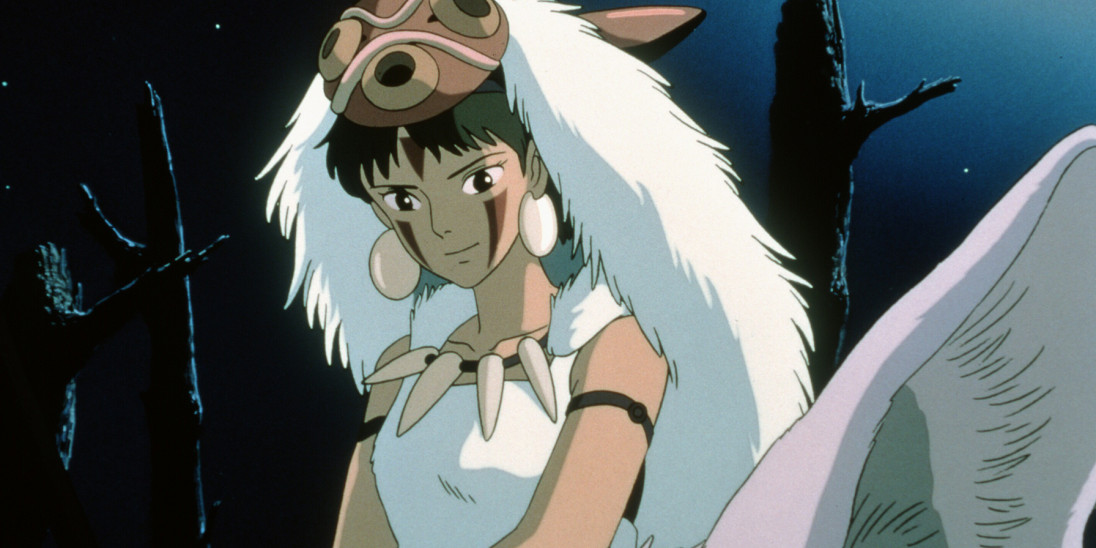

Princess Mononoke (1997)

Princess Mononoke (1997): A Masterpiece of Animation and Environmentalism

Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke (1997) is not just a film, but an experience—a profound exploration of humanity’s complex relationship with nature, the clash between industrial progress and environmental preservation, and the moral dilemmas that lie at the heart of these conflicts. As one of Studio Ghibli’s finest works, Princess Mononoke stands as a rich and ambitious epic that blends fantasy, folklore, and social commentary, all wrapped in a beautifully animated package.

Plot Overview: A Battle Between Nature and Man

Set in the late Muromachi period of Japan (approximately 14th to 16th centuries), Princess Mononoke follows the journey of Ashitaka, a young warrior cursed by a boar demon infected by an iron ball. Ashitaka’s curse, which slowly poisons him, leads him to seek the source of the demon’s wrath in order to find a cure. His quest takes him into the heart of the wilderness, where he encounters the mysterious and vengeful wolf-girl, San, also known as Princess Mononoke, and becomes entangled in a conflict between the human inhabitants of Iron Town, led by Lady Eboshi, and the animal gods of the forest, including the boar god, Okkoto, and the wolf goddess, Moro.

At its core, Princess Mononoke is a story about the destructive impact of human expansion on the natural world, the consequences of industrialization, and the complex roles humans play in both protecting and destroying the environment. Ashitaka, who tries to mediate between the two sides, must confront the fundamental question: Can the destruction of nature ever be justified, or can balance between mankind and the environment be achieved?

Themes: Environmentalism and the Duality of Humanity

One of the most compelling aspects of Princess Mononoke is its deep, thoughtful engagement with environmental themes. The film does not take a simplistic “good vs. evil” approach. Instead, it acknowledges the complexities of the forces involved. Lady Eboshi, the leader of Iron Town, represents industrial progress and human ingenuity. She is not depicted as a villain but rather as a determined, forward-thinking leader who aims to improve the lives of her people, particularly marginalized women and lepers. Her development of Iron Town is a response to the need for economic growth and technological advancement. However, her methods are violent and destructive, as she seeks to extract iron from the forest, which leads to the destruction of the very habitat that sustains the forest spirits and gods.

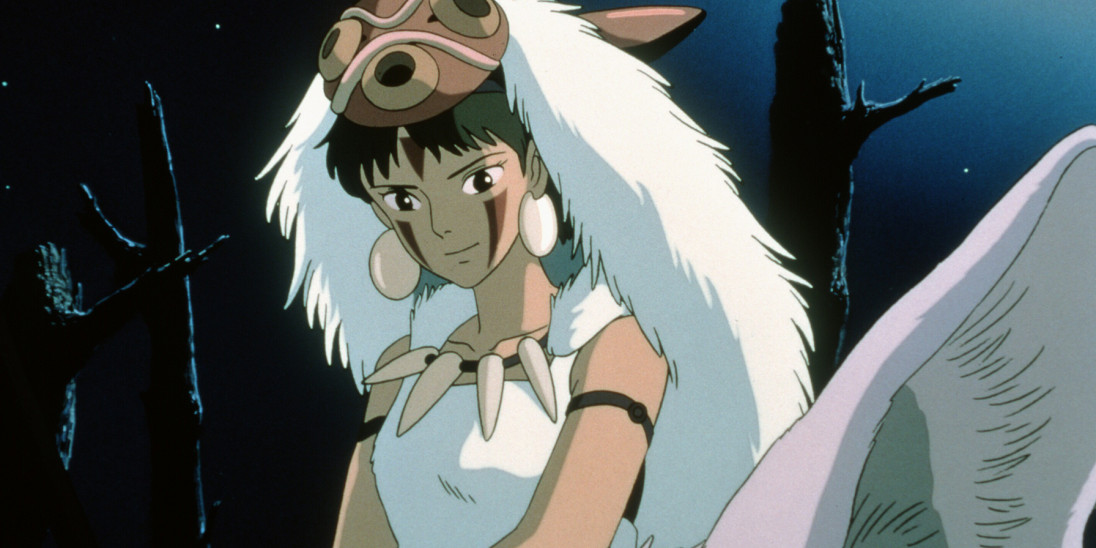

On the other side of the conflict, the animal gods of the forest, including the boar god Okkoto and the wolf goddess Moro, represent nature in its primal, untamed form. They are portrayed as noble but vengeful beings, struggling to protect their homeland from human encroachment. The character of Princess Mononoke, or San, encapsulates the anger and pain of nature itself, a young woman raised by wolves, who has sworn to avenge the destruction of her forest home. Her relationship with Ashitaka is one of tension and understanding, as they both recognize the righteousness of their respective causes but also understand the futility of blind vengeance.

At the heart of this conflict is Ashitaka, who is caught between these two forces. He is a character of remarkable empathy and compassion, seeking not to destroy, but to reconcile. His curse symbolizes the harm caused by the unbridled conflict between humans and nature, and his journey represents the possibility of healing, both for himself and the world around him.

Miyazaki’s handling of these themes is nuanced and mature. The film does not present a simple solution to the environmental crises it portrays. Instead, it offers a reflection on the inherent conflict between progress and preservation, and the difficult choices that must be made in a world where both are necessary for survival. The film’s refusal to offer clear moral answers is one of its greatest strengths, inviting viewers to reflect on their own relationships with nature, industry, and the environment.

Visual and Artistic Mastery

Princess Mononoke is, of course, famous for its stunning animation. Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli have always been known for their exceptional craftsmanship, and this film is no exception. The lush forests, the majestic, powerful animals, and the intricate designs of the characters and settings all contribute to the film’s immersive world-building. The contrast between the serene, beautiful landscapes of the forest and the grim, industrial aesthetics of Iron Town is striking, underscoring the thematic dichotomy at the heart of the story.

One of the most iconic images in the film is the giant boar god, Okkoto, whose majestic and terrifying presence reflects the immense power of nature. The animators’ attention to detail in bringing these fantastical creatures to life—whether the wolf god Moro, the boar, or the spirit of the forest—is breathtaking. The designs are not only beautiful but also convey the personality and power of these beings, making them feel alive and real.

The film also employs traditional 2D hand-drawn animation, which, while somewhat outdated in the age of CGI, gives the film a timeless quality that has not diminished over the years. Every frame feels rich with detail, and the motion of characters and creatures is fluid and lifelike. The attention to the smallest elements, like the rustling of leaves, the movement of clouds, or the flicker of firelight, makes the world feel tangible and immersive.

Music and Sound Design: A Perfect Complement

The music of Princess Mononoke, composed by Joe Hisaishi, is one of the key elements that elevates the film to another level. Hisaishi’s score is sweeping and emotive, perfectly complementing the film’s epic scope and emotional depth. The music moves seamlessly from gentle, meditative moments to intense, stirring crescendos, matching the tone of the film’s various emotional beats.

One of the standout pieces is the main theme, which is both haunting and beautiful. It captures the essence of the film’s themes of conflict, loss, and hope. The use of traditional Japanese instruments, like the shakuhachi (bamboo flute) and koto (zither), creates a distinctly Japanese atmosphere, grounding the fantasy world in real-world cultural references. The music becomes a character in its own right, amplifying the emotional weight of the narrative.

The sound design in Princess Mononoke is equally impressive. The soundscape of the forest, with the sounds of rustling leaves, distant animal calls, and the whisper of wind, helps to immerse the audience in the natural world. The sounds of Iron Town—metal clanging, machinery whirring, and the clatter of industry—create a sharp contrast, reinforcing the theme of nature versus industry.

Character Development: Complex and Multi-Dimensional

Miyazaki has long been praised for creating complex, multi-dimensional characters, and Princess Mononoke is no exception. Each character in the film is driven by a clear sense of purpose and internal conflict, making them relatable and human, even if they are not strictly human in form.

Ashitaka, as the protagonist, is a beacon of compassion, and his journey is one of self-discovery and healing. His internal struggle—between his growing affection for San and his sense of responsibility to both humans and the natural world—makes him one of Miyazaki’s most nuanced and empathetic characters. Ashitaka is neither perfect nor all-knowing; he is simply a person trying to do what is right, even when the answers are unclear. His ability to empathize with both sides of the conflict allows him to see beyond the binary divisions of good and evil.

Lady Eboshi is another complex character. While she may seem like the film’s antagonist, her motivations are rooted in a desire to improve the lives of her people, particularly women and the sick. She has built Iron Town as a place of progress, but at a cost. Her willingness to destroy nature to build her industrial empire reflects the harsh realities of human survival, but her character is not painted with the brush of villainy. She is a product of her time and circumstances—indifferent to the spiritual beliefs of the forest, yet deeply concerned with human well-being.

San, or Princess Mononoke, is perhaps the most tragic figure in the story. Raised by wolves and deeply connected to the forest, her hatred for humans is intense, yet beneath her fierce exterior is a deep pain. She represents nature’s fury, but her story also reflects the anguish of losing one’s home and the struggle to find peace in the face of overwhelming destruction. Her relationship with Ashitaka is central to the narrative, as their growing understanding of each other shows that the divide between humanity and nature may not be as unbridgeable as it first appears.

Conclusion: A Film of Timeless Relevance

Princess Mononoke is a cinematic masterpiece that continues to resonate with audiences today, nearly three decades after its release. Its exploration of environmental destruction, industrialization, and the need for balance between nature and humanity is just as relevant now as it was in the late 1990s—and perhaps even more so, as global environmental concerns become increasingly urgent.

Miyazaki’s ability to weave fantasy, folklore, and social commentary into a cohesive and emotionally resonant narrative is a testament to his genius as a storyteller. The film is visually stunning, musically profound, and thematically rich, offering not only a thrilling adventure but also a deep philosophical meditation on the struggles between progress and preservation.

Princess Mononoke is not just a film to be watched, but a film to be experienced. Its emotional depth, thematic complexity, and visual beauty ensure its place as one of the greatest animated films of all time. For those who seek more than just entertainment from cinema, Princess Mononoke is an unforgettable journey into the heart of nature, humanity,